The Lenora, Mt. Sicker Railway Was an ‘Engineering Marvel’

‘The driving of the last spike of the Lenora-Mount Sicker Railway extension on the smelter site at Crofton last week will be a memorable event in the industrial annals of the Island.’ –Crofton Gazette and Cowichan News, May 8, 1902.

‘Of the myriad mining railroads built around the turn of the [last] century, few could match the Lenora, Mt. Sicker in either the gleaming beauty of its diminutive narrow-gauge Shay locomotives or its harrowing use of thirteen percent grades, seventy-five degree curves and triple switchbacks.’–Elwood White and David Wilkie, Shays On the Switchbacks.

‘The thought occurred to everyone in the party, if the brakes had failed or become unmanageable, what a terrible trip they would have taken to eternity.’ –Colonist.

* * * * *

In last week’s ramble about this week’s post I wrote of driving home from Chemainus and seeing, ever so fleetingly while also trying to keep my eye on the road, that one of the last surviving stretches of this historic railway had been just been dug up for a new driveway.

(It’s on the west side of the highway immediately after you navigate, southbound, the Mount Sicker (Red Rooster) intersection.)

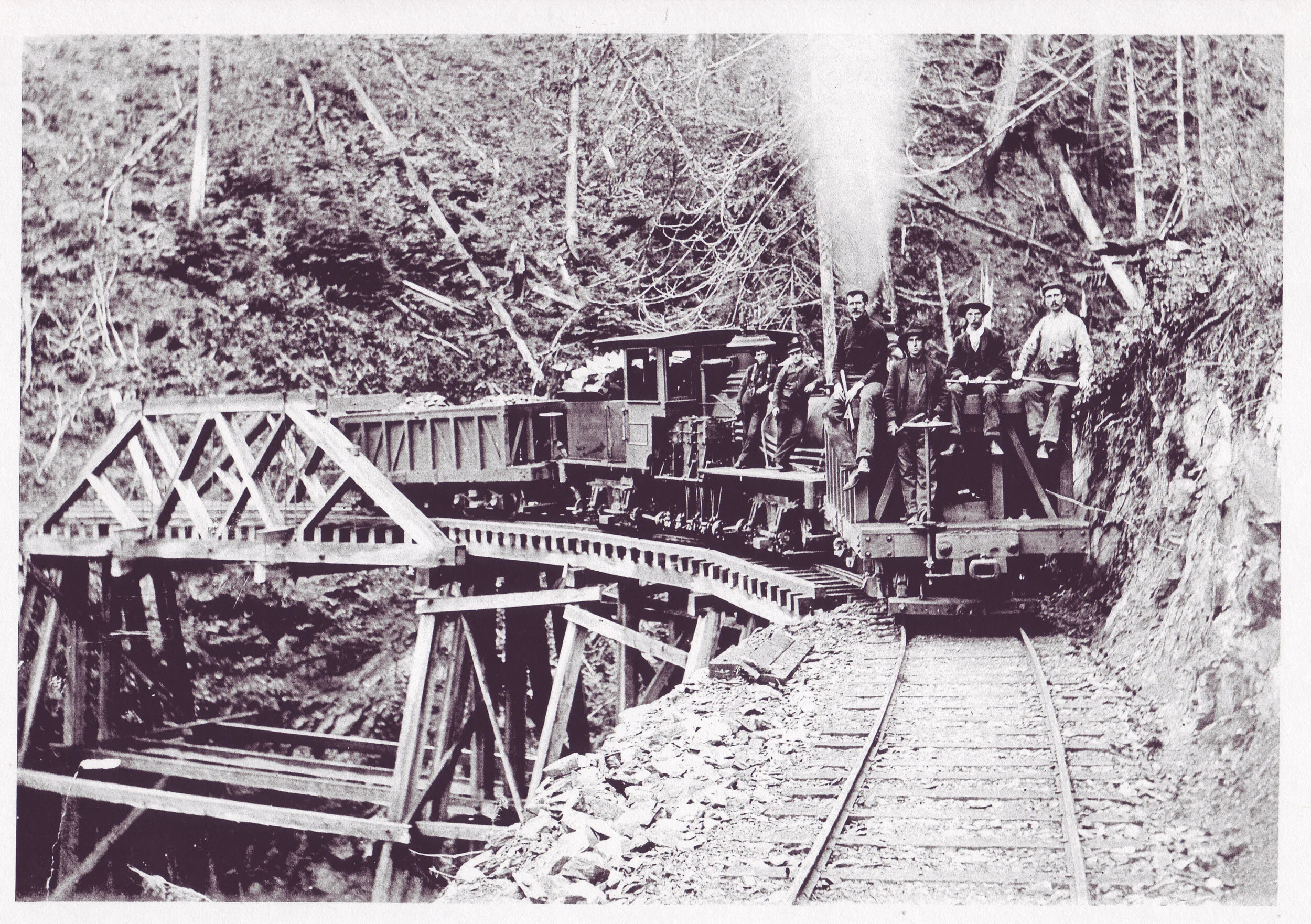

Elwood White’s photo of the Lenora Mount Sicker Railway’s No. 2 Shay crossing over Nugget Creek. There’s nothing to be seen there today.

And I cursed Progress for having claimed yet another historical icon.

Many of you will know that the copper mining activity on Mount Sicker at the turn of the last century has intrigued me from even before I moved to the Cowichan Valley. I’ve since written about it in newspaper articles, columns and even a book, Riches to Ruin: The Boom to Bust Saga of Vancouver Island’s Greatest Copper Mine, from which much of today’s story is taken.

To tell the incredible story of Mount Sicker in as few words as possible (my 2007 book is 300 pages):

In the mid-1890s several American prospectors from Washington State, likely inspired by the world-shaking Klondike gold rush, detected promising signs of copper on Little Sicker Mountain. A new partner, Harry Smith, an Englishman who lived in Port Townsend, made the big find that led to two phenomenally rich mines, the Lenora and the Tyee.

Both ended up being owned by mostly British syndicates. But both were, in reality, chasing the same rich but limited ore body, the Lenora from below, the Tyee from above, and it hastened their doom. (It was all over in just 10 years although both mines were re-worked as one during the Second World War for their lead and zinc content.)

But our interest, today, is in the Lenora, which was managed by Henry Croft, brother-in-law of James Dunsmuir the wealthy coal mining magnate who also owned the E&N Railway which passes just below and to the east of Big Mount Sicker.

At first Henry had to haul his ore (really high-grade copper with a lesser mix of gold and silver) down the mountain by horse-drawn wooden cars on wooden rails. All very crude, very inefficient and very expensive.

So Henry, who seems to have dreamt in Technicolor and who seems to have decided that Dunsmuir was gouging him with his freight rates, made the decision to haul the ore from Mount Sicker to a new deep-sea port (and, later, a smelter) which, not unfairly, became Crofton.

To do this he had to carve a narrow gauge railway grade down the steep, hummocky slopes of both Mount Sickers, across the wetlands of Westholme Valley and over Mount Richards. Depending upon whether one views life as a glass half-full or a glass half-empty, it was either an engineer’s dream project or a nightmare come true!

But there was something about that period of B.C. history that was unique; there’s never been a time quite like it since, for all of the technological changes that have transformed our lives in subsequent decades. (Perhaps the postwar boom and the mega-projects of the 1950s came close.) That was when Science was the new-found God, when no engineering problem—this was before mechanization replaced human brawn—couldn’t be beaten by human ingenuity and money.

So it was with Henry Croft: he needed a railway, he would build one. And he did.

The LMSRR’s No. 1 locomotive was soon put to work hauling high-grade ore from the Lenora Mine.

There, I’ve set the stage for today’s story...

Although miles of this old railway grade have survived the combined assaults of loggers, road builders, fires and Mother Nature, for all practical purposes, the historic LMSRR is another historical footnote.

As part of the right-of-way passed through Eve’s Provincial Park, on the western slope of Mount Richards, the park’s board of directors commissioned an interpretive signboard, which was unveiled at a special ceremony in 2003.

One of the photographs on display was courtesy of the late Elwood White, co-author with the late David Wilkie of Shays On the Switchback, a history of this narrow gauge railway published in the 1960s. The photo depicted No. 2 Shay, with two ore cars, crossing the trestle over Nugget Creek. It’s a great scene but, alas, nothing like what’s there today. Just a few rotting timbers and lengths of steel rod that held the small, single-span trestle together are to be found in the overgrown creek bed, and it takes real imagination to match today’s scene with that of yesteryear.

Henry Croft originally tried hauling his Lenora Mine ore down the mountain to the E&N Railway at Mount Sicker Siding by means of horse and wagon, then by a three-mile-long tramway. Because the cars were drawn by horses and its rails were of wood with straps of iron for a bearing surface, the system was slow, subject to failure and the ore began to pile up at the mine.

So Croft decided to build a narrow gauge railway line to meet the E&N mainline, a distance of six miles because it involved numerous curves, some of them up to 50 degrees–where it crossed Nugget Creek, no less than 75 degrees–down Haggarty Hill. This was a drop of almost 700 feet in less than a mile, then on down the western slope of Mount Sicker to the Westholme Valley floor. J.R. Irving laid out this challenging route and 100 navvies from Victoria did the clearing and grading, starting at the mine and working their way down the mountain to the link with the E&N.

The little line, termed an engineering marvel, took four months to grade and cost just under $60,000.

Its first engine, hence its being designated in gold leaf, Lenora No. 1, a 10-ton Shay from the Lima Locomotive and Machine Works in Lima, Ohio, was described by authors White and Wilkie as a “machine of rare beauty”. But the Lenora No. 1 was small, able to handle just a single 10-ton, or two self-dumping five-ton loaded ore cars at a time. On Jan. 21, 1901, under command of engineer Aaron Garland and conductor R.L. Gibbs, she made her first run and was soon hard at work, hauling high-grade ores down to the E&N.

Today, this view of the busy Lenora Mine and the start of the Lenora Mount Sicker Railway looks like a gravel pit with a creek running through it. —Elwood White photo

Riding the Mount Sicker railway was a memorable experience, some grades being so steep and twisting that brakemen had to ride shotgun on each car, at the ready to apply the brakes, and steeper grades had to be sanded for extra traction. Although there was no accommodation for passengers, the Colonist cheekily urged its readers to ride an ore car down the slopes of Mount Sicker, while enjoying the spectacular scenery en route to the Crofton smelter. Having been instructed by the conductor to “hang on anywhere we could,” the Colonist party did so, “as, with a warning whistle, the little engine began to push, puff and fume up the big hill to an elevation of well over a thousand feet from the starting point... As the straining ore train skirted the edge of the mighty canyon dividing Mt. Brenton and Mt. Sicker, sometimes the car was at such an angle that a chunk of ore would roll off while the tenderfoot passengers were compelled to sit on the side of the oscillating vehicle with their feet dangling over the precipice.

“If they looked while rounding the sharp curves, the tall firs skirting the Chemainus River looked like animated toothpicks moving in the mazes of some strange dance... To those unaccustomed to the hills it was out of the question to close their eyes so they just stared at the appalling immensity of nature.

“The thought occurred to everyone in the party, if the brakes had failed or become unmanageable, what a terrible trip they would have taken to eternity.”

When Croft decided to build a smelter at Crofton, he had to extend his railway. The Crofton Gazette reported, March 6, 1902: “The Lenora Mt. Sicker company have given out a contract for 2,000 five and six-inch ties to be ready for the immediate construction of their railway extension from Mt. Sicker siding to Crofton. The laying of the rails has already been begun, and trains will be running into Crofton probably before the end of the month.”

Construction proceeded smoothly, if negotiations between Croft and Dunsmuir for crossing the E&N hadn’t. (Dunsmuir had a long track record of fighting off those who wanted to cross his right-of-ways.) While the federal government did come down on Croft’s side, he made a mortal enemy in his brother-in-law (which would cost him dearly in the long run) and he was put to the cost of building a timber overpass, rather than having a level, cheaper crossing by means of a switch.

Nevertheless, just two weeks after giving a contract for railway ties, “The trestle and bridge at Mt. Sicker siding are being rapidly pushed to completion now that permission for the crossing of the E. & N. railway has been granted by the Dominion government, at Ottawa. The lumber will be supplied from Mr. F. Lloyd’s mills at Westholme. Some three miles of rails are now lying at Ladysmith, and the balance necessary to complete the laying of this line will be on the ground in less than two weeks. A new locomotive now standing in Vancouver will shortly be shipped across and delivered at Mt. Sicker [S]iding, to be used for hauling ore from that point to the smelter at Crofton.”

On May 1st the Gazette jubilantly reported: “The rails are now laid into Crofton, and trains are running daily between Mount Sicker and the smelter.

“The opening was celebrated on Saturday last, when a party of newspaper and mining men journeyed up the line from Crofton to Mount Sicker in a car gaily decorated with flags and drawn by one of the Lenora company’s powerful little 20-ton geared engines, which was festooned with flowers for the occasion. Mr. Croft entertained the party at the Mount Sicker Hotel, and the event was a memorable one, being as it was the practical inauguration of a new stage of development on the Island.”

Just a week later, “Mr. Henry Croft brought a distinguished party to Crofton on Friday to celebrate the completion of the Mount Sicker Railway extension to the smelter site at Crofton. The ceremony of driving the last spike was performed by Mrs. Croft, in the presence of Sir Richard and Lady Musgrave, Mrs. Snowden, Miss Bryden, Mr. and Mrs. D.S. Fotheringham, Admiral Rose, Capt. L. Thompson, P.L.S., Messrs. J. Croft, Fred. Young, George Williams, J.C. Lang and many others. Mr. Croft’s party arrived from Mount Sicker in a gaily decorated car and the scene was a bright one, the importance of the occasion being thus commemorated by a quiet but pretty social ceremonial.

“The rails are now laid to the point on the smelter site where the line will converge in two branches to the ore bins. To reach these it will be elevated the last part of the way on trestles, and the work of this construction is now proceeding. From a point a few hundred yards further back, railway connection will be made with the wharf; and the town station will be situated at the foot of Joan Avenue, close to the shore. The rails will be laid here as soon as they are delivered, and they are daily expected.

“The importance of the work thus being completed can hardly as yet be estimated. The mineral properties of Mount Sicker, Mount Brenton and Mount Richards are now connected with the Crofton smelter, which in a month’s time will be receiving ores, and two months hence will be treating them, and a future of brilliant mining and industrial promise not only for the Cowichan district, but for the whole Island has been unobtrusively inaugurated by the little party of ladies and gentlemen who, at Mr. Croft’s invitation, journeyed down to see the new town and to grace the occasion.

“A year or two hence, when the Crofton smelter will have fulfilled its industrial promise, those who were present last week will doubtless look back upon their participation in this simple ceremony with vivid emotions of pride and pleasure.”

The Gazette was determined that its readers grasp the full significance of this great event:

“The last spike has been driven on the Lenora-Mount Sicker Railway extension, and this wonderful little line now provides direct communication between the mines of Mount Sicker and district and the Crofton smelter. The social ceremony with which Mr. Henry Croft and a party of friends celebrated the completion of the work would alone have distinguished the occasion, but far deeper thoughts occur to us in connection with this important accomplishment. Direct communication is now established between the foremost mining district on the Island and the Crofton smelter, whereby copper ores may now be transported in a few hours and with a minimum of cost to the works that will reduce them to blister copper.

“The days of waiting are over. Mine-owners need no longer make provision for innumerable delays in transportation and large costs likely to be incurred in shipping their mineral products to far-off foreign smelters. These delays and this expenditure have hitherto contributed to render impossible the shipment of low-grade ores from many otherwise promising mines, and the mere thought and dread of them has militated against development work on new mineral claims. This condition of affairs has now changed. The smelting industry has been practically inaugurated on Vancouver Island.

“And what does this mean, especially to the Cowichan district? To the mining industry it means a new stimulus, fresh developments, and a correspondingly increased output. It provides brighter hopes for prospectors, with a better chance of disposing of their claims, because capitalists will now be more ready to invest in the country. For labour it means more hands at work and the certainty of the continuance of work. In a word it spells prosperity. To the farmer it promises new markets for his agricultural products, and to the merchant it opens an avenue of steady sale for his merchandise. To the languishing mining broker and the hard-up real estate agent it equally means business. In a word, again we repeat it foreshadows prosperity. The driving of the last spike of the Lenora-Mount Sicker Railway extension on the smelter site at Crofton last week will be a memorable event in the industrial annals of the Island.”

Croft placed two larger Shay locomotives on the line, the secondhand No. 2 and the new No. 3. This was the engine that, with Al Parkinson as engineer, Albert Holman as fireman and James Porter as conductor, hauled the first train of ore to the smelter. To handle the standard gauge rail cars that utilized the barge service at the company dock in Crofton, yet a fourth locomotive had to be acquired, this one a 15-year-old standard gauge Forney that later saw service with John Coburn’s New Ladysmith Lumber Company at East Wellington.

This is the view taken a few years ago from just above the ore pens shown in the right background of the preceding archival photo. Jennifer is looking towards the east at what appears to be a massive anthill. It’s the ore pile from the competing Tyee Mine.

All of this represented a magnificent achievement (not to mention expense) in view of the series of challenging switchbacks on Mount Richards that had to be engineered. Anyone who has ever hiked this stretch of the abandoned grade (you can still see a few stretches of beautifully crafted rock cribbing) can appreciate what was involved–not just in the building of this railway, but in the day-to-day operation of heavy ore trains.

That said, while watching or downloading the news or reading a real newspaper, you might consider looking at current happenings the way I do, through a rear view mirror, by linking them to the past. You don’t have to have a professional historian’s broad knowledge to read about, say, an old building that’s being demolished to wonder at what stories it could tell, and filling in some of the blanks if you know them. Or to link some other event or physical landmark to a previous era. In short, it simply involves looking back into time and reflecting. So many things have changed in your lifetime and, yes, the world really is “going to h—”.

But so what? Think of the good old days and savour what you can of them. As I’ve often said, they’re not making them any more. When, just a few short years later, the Lenora Mine went into receivership, the costs of building the LMSRR were a contributing factor. With the mine went its little railway. After the 1 and 2 were used for a short time by new Lenora owners who cleaned out the last easily accessible ores, the No. 2 barely escaped the scrap pile when she was purchased for use as a logging ‘locie’. The No. 3, rebuilt after it was damaged by inexperienced miners who attempted to run her down the mountain over neglected tracks, went on to scald two of her engineers to death.

The tracks were torn up in 1912. As had the builders before them, they started at the mine and worked their down the mountain, pulling up the rails and loading them onto one of the flatcars which was drawn by a team of horses. Most of the rail cars were burned for their hardware on the beach at Crofton and hauled away by barge.

There was at least one ray of sunshine in all this doom and gloom, the Leader having reported in December 1907 the Christmas Day wedding–Mount Sicker Siding’s first and likely only–of Warren Wildes and Miss Margaret Mills.

Mount Sicker’s mines and two townships, Crofton’s smelter and the Lenora Mount Sicker Railway are all history now. But their memory lives on at Eves Provincial Park, Westholme, with its single length of restored railway track.

There are, of course, other reminders if one knows where to look. Although the building of the Island Highway obliterated all traces of where the grade exited at Mount Sicker Siding to carry on to Crofton, stretches of it are clearly visible in the front yards of several houses above the highway and in a farmer’s pasture (until a few weeks ago!). Later used as a lumber mill, Sicker Siding has homes now. Of the trestle that spanned what is today a low-lying pasture, there’s nothing to be seen, either. You have to head across, due east, to pick up the grade again where the ground begins to rise and becomes the western slope of Mount Richards.

Back on the northern shoulder of Mount Sicker, stretches of railway grade more or less parallel the road up the winding incline. The author is indebted to local farmer George Compton for taking the time in the summer of 2007 to point out a large cedar stump immediately beside the grade that had been deeply notched. Not spring-board notched by a logger, but notched to allow something that stuck out from the train to pass by without catching! Some unknown LMSRR navvy had seen that this was much easier than removing the stump at the end of an aptly-named misery whip, a bucksaw.

Now, I hope, you understand why I mourn the loss of that little curve of LMSRR grade, just a few hundred feet or so, that has just been obliterated for a driveway. I bet you the owner didn’t even know its significance.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.