My First Christmas Dinner in Victoria

by D.W. Higgins

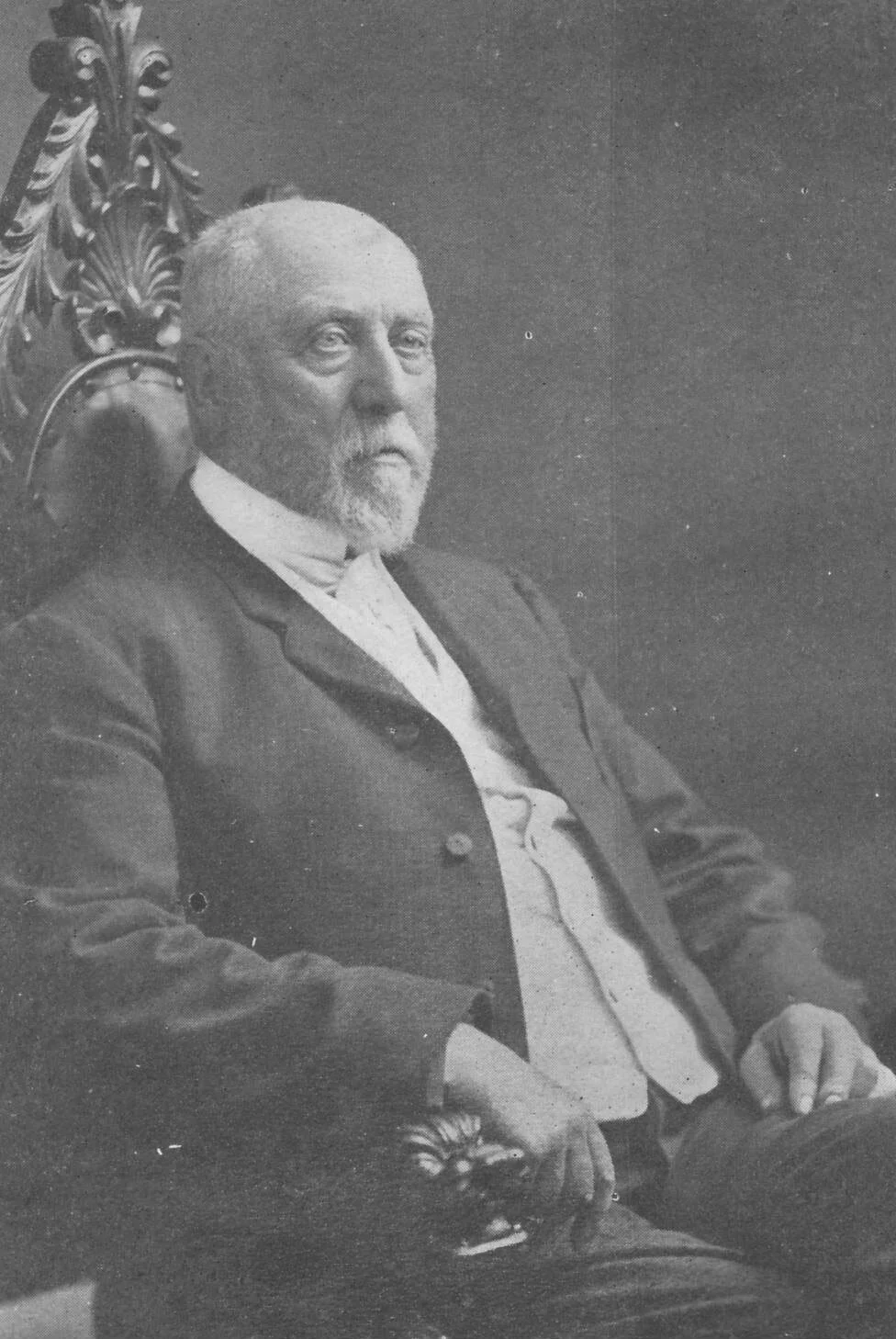

D.W. Higgins

Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock and it shall be opened unto you. For everyone that seeketh receiveth; and he that seeketh findeth; and to him that knocketh, it shall be opened.”—Matthew vii, 7, 8.

On the 22nd day of December, 1860, nearly forty-four years ago, I sat in the editorial rooms of the Colonist office on Wharf Street preparing a leading article. Mr. DeCosmos, the editor and owner, had contracted a severe cold and was confined to his room at Wilcox’s Royal Hotel, so the entire work of writing up the paper for that issue devolved upon me.

The office was a rude one-storey affair of wood. It had been erected by a merchant early in 1858, and when he failed or went away the building fell into Mr. DeCosmos’s hands. On the 11th of December, 1858, Mr. DeCosmos established the Colonist, which has ever since filed a prominent and honourable position in colonial journalism.

Our office, as I have remarked, was a rude affair. The editorial room was a small space partitioned off from the composing-room, which contained also the little hand-press on which the paper was printed. A person who might wish to see the editor was forced to pick his way through a line of stands and cases, at which stood the coatless printers who set the type and prepared the forms for the press.

The day was chill and raw.

A heavy wind from the southwest stirred the waters of the harbour and hurling itself with fury against the front of the building made the timbers crack and groan as if in paroxysms of pain. A driving rain fell in sheets on the roof, and drops of water which leaked through the shingles fell on the editorial table, swelled into little rivulets, and leaping to the floor chased each other across the room, making existence in the office uncomfortably damp.

As I wrote away in spite of these unpleasant surroundings, I was made aware by a shadow that fell across my table of the presence of someone in the doorway. I raised my eyes and there stood a female—a rare object in those days, when women and children were hardly ever met upon the streets, much less in an editorial sanctum. I rose to my feet at once and removed my hat. In the brief space of time that elapsed before the lady spoke I took her all in.

She was a woman of scarcely forty, I thought, of medium height, a brunette, with large, coal-black eyes, a pretty mouth—a perfect Cupid’s bow—and olive-hued cheeks. She was richly dressed in bright colours, with heavy broad stripes and space-encircling hoops after the fashion of the day. When she spoke it was in a rich, well-rounded tone.

Taken all in all, I sized the lady up as a very presentable person. When I explained to her in response to an enquiry that the editor was ill, she said that she would call again, and went away after leaving her card. Two days later, on the 24th of December, the lady came again.

“Is the editor still ill?” she asked.

“Yes; but he will be here in the course of a day or so.”

“Ah! well, that is too bad,” she said. “My business is of importance and cannot bear delay. But I am told that you will do as well.”

I assured the lady that I should be glad to assist her in any way. Thanking me, she began:

“My name is Madame Fabre. My husband, who was French, is dead—died in California. I am a Russian. In Russia I am a princess.” (She paused as if to watch the impression her announcement had made.)

“Here I am a mere nobody—only Madame Fabre. I married my husband in France. We had much money and my husband went into quartz mining at Grass Valley [California]. He did not understand the business at all We lost everything. Then he died” (and she drew a lace handkerchief from her reticule and, pressing it to her eyes, sighed deeply.) Alas! yes, Emil passed from me and is now, I trust, in heaven. He left me a mountain of debts and one son, Bertrand, a good child, as good as gold, very thoughtful and obedient. May I call him in? He awaits your permission without.”

I replied, “Certainly,” and stepping to the door she called, “Bertrand! Bertrand! my child, come here, and speak to the gentleman.”

I expected to see a curly haired boy of five or six years, in short trousers, a beaded jacket and fancy cap, whom I would have taken on my knee, toy with his curls, ask his name and age and give him a “bit,” with which to stuff his youthful stomach with indigestible sweetments.

Judge of my surprise when, preceded by the noise of a heavy tread, a huge youth of about seventeen, bigger and taller than myself, and smoking a cigar, appeared at the opening and in a deep, gruff voice that a sea captain or a militia commander would have envied, asked—

“Did you call, mamma?’

“Yes, my dear child,” she sweetly responded, “I wish to introduce you to this gentleman.”

The “child” removed his hat, and I noticed that his hair was cut close to the scalp. Having been duly introduced, at my request he sat down in my chair, while I took a seat on the end of the editorial table, which was very rickety, and would scarcely bear my weight at the present day.

The mother gazed at her so fondly for a moment and then proceeded:

“Bertrand’s fortune was swallowed up in the quartz wreck, but he is very sweet and very patient, and never complains. Poor lad, it was hard upon him, but he forgives all—do you not, dear?”

“Yes,” rumbled the “child” from the pit of his stomach; but the expression that flitted across his visage made me think that he would rather have said “No” had he dared.

“That being the case I shall now explain the object of my visit. As I have said, we have lost everything—that is to say, our income is so greatly reduced that it is a matter of not more than $1,000 a month. Upon that meagre sum my dear boy and I contrive to get along by practising the strictest economy consistent with our position in life. Naturally we wish to do better and then go back to Russia and live with the nobility. Do we not, Bertrand?”

“Yes, “rumbled the “child” from his stomach again, as he lighted a fresh cigar.

“Well now, Mr. H.,” the lady went on, “I want an adviser. I ask Pierre Manciot of the French Hotel and he tells me to see his partner, John Sere; and Mr. Sere tells me to go to the editor of the Colonist. I came here. The editor is ill. I go back to Mr. Sere and he says, ‘See D.WH., he will set you all right.,’ So I come to tell you what I want.”

She paused for a moment to take a newspaper from her reticule and then continued:

“After my husband died and left the debts and this precious child (the “child” gaze abstractedly at the ceiling while he blew rings of smoke from his mouth) “we make a grand discovery. Our foreman, working in the mine, strikes rich quartz, covers it up again, and tells no one but me. All the shareholders have gone—what you call ‘busted,’ I believe. We get hold of so many shares cheap, and now I come here to get the rest. An Englishman owns enough shares to give him control—I mean that out of 200,000 shares I have got 95,000 and the rest this Englishman holds. We have traced him through Oregon to this place, and we lose all sight of him here.” (Up to this moment I had not been particularly interested in the narration.) She paused, and laying a neatly-gloved hand on my arm proceeded:

“You are a man of affairs.”

“Ah! yes. You cannot deceive me. I see it in your eyes, your face, your movements. You are a man of large experience and keen judgment. Your conversation is charming.”

As she had spoken for ten minutes without giving me an opportunity to say a word, I could not quite understand how she arrived at this estimate of my conversational powers. However, I felt flattered, but said nothing.

Pressing my arm wither hand, she went on:

“I come to you as a man of the world. (I made a gesture of dissent, but it was very feeble, for I was caught in her web.) “I rely upon you. I ask you to help me. Bertrand—poor, dear Bertie—has no head for business. He is too young, too confiding, too—too—what you English people call simple—no, no, too good—too noble—he takes after my family—to know anything about such matters, so I come to you.”

Was it possible that because I was considered unredeemably bad I was selected for this woman’s purpose? As I mused, half disposed to get angry, I raised my head and my eyes encountered the burning orbs of Madame, gazing full into mine. They seemed to bore like gimlets into my very soul. A thrill ran through me like the shock from an electric battery, and in an instant I seemed bound hand and foot to the fortunes of this strange woman.

I felt myself being dragged along as the Roman Emperors were wont to draw their captives through the streets of their capital. I have only a hazy recollection of what passed between us after that, but I call to mind that she asked me to insert a paragraph from the Grass Valley newspaper to the effect that the mine (the name of which I forget) was a failure and that shares could be bought for two cents. When she took her leave I promised to call upon her at the hotel.

When the “child” extended a cold, clammy hand in farewell I felt like giving him a kick—he looked so grim and ugly and patronizing. I gazed into his eyes sternly and read there deceit, hypocrisy and moral degeneration. How I hated him!

The pair had been gone for several minutes before I recovered my mental balance and awoke to a realization of the fact that I was a young fool who had sold himself (perhaps to the devil) for a few empty compliments and a peep into the deep well of an artful woman’s blazing eyes. I was inwardly cursing my stupidity while pacing up and down the floor of the “den” when I heard a timid knock at the door. In response to my invitation to “come in” a young lady entered. She was pretty and about twenty years of age, fair, with dark blue eyes and light brown hair. A blush suffused her face as she asked for the editor. I returned the usual answer.

“Perhaps you will do for my purpose,” she said. “I have here a piece of poetry.”

I gasped as I thought, “It’s an ode on winter. Oh, Caesar!”

“A piece of poetry,” she continued, “on Britain’s Queen. If you will read it and find it worthy a place in your paper I shall be glad to write more. If it is worth paying for I shall be glad to get anything.”

Her hand trembled as she produced the paper.

I thanked her, telling I would look it over and she withdrew. I could not help contrasting the first with the last visitor. The one had attracted me by her artful and flattering tongue, the skilful use of her beautiful eyes and the pressure of her hand on my coat sleeve; the other by the modesty of her demeanour. The timid shyness with which she presented her poem had caught my fancy. I looked at the piece. It was poor; not but what the sentiment was there—the ideas were good, but they were not well put. As prose it would have been acceptable, but as verse it was impossible and not worth anything.

The next was Christmas Day. It was my first Christmas in Victoria.

there was a wooden verandah or shed that extended from the front of the building to the outer edge of the sidewalk. One might walk along any of the down-town streets and be under cover all the way. They were ugly, unsightly constructions, and I joined the aldermanic board and secured the passage of an ordinance that compelled their removal.

Along these verandahs on this particular Christmas morning evergreen boughs were placed, and the little town really presented a very pretty and sylvan appearance. After church I went to the office and from the office to the Hotel de France for lunch. The only other guest in the room was a tall, florid-faced young man somewhat older than myself. He occupied a table on the other side of the room. When I gave my order the landlord remarked, “All the regular boarders but you have gone to luncheon and dinner with their friends. Why not you?”

“Why,” I replied with a quaver in my voice, “the only families that I know are dining with friends of their own whom I do not know. I feel more homesick to-day than ever before in my life and the idea of eating Christmas dinner alone fills me with melancholy thoughts.”

The man on the other side of the room must have overheard what I said, for he ejaculated:

“There’s two of a kind. I’m in a similar fix. I know no friends here—at least none with whom I can dine. Suppose we double up?”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Why, let us eat our Christmas dinner together and have a good time. Here’s my card and here’s a letter of credit on Wells, Fargo’s agent to show that I am not without visible means of support.”

The card read, “Mr. George Barkley, Grass Valley.”

“Why,” I said, “you are from Grass Valley. How strange! I saw two people yesterday—a lady and her ‘child’—who claimed to have come from Grass Valley.”

“Indeed,” he asked, “what are they like?”

“The mother says she is a Russian princess. She calls herself Madame Fabre and says she is a widow. She is very handsome and intelligent, and,” I added with a shudder, “has the loveliest eyes—they bored me through and through.”

My new-found friend faintly smiled and said, “I know them. Bye-and-by, when we get better acquainted, I shall tell you all about them.”

After luncheon we walked along Government Street to Yates Street, and then to the Colonist shack. As I placed the key in the lock I saw the young lady who had submitted the poetry walking rapidly towards us. My companion flushed slightly and lifting his hat extended his hand, which the lady accepted with hesitation. They exchanged some words and then the lady, addressing me, asked, “Was my poem acceptable?”

“To tell you the truth, Miss—Miss—“

“Forbes,” she interjected.

“I have not had time to read it carefully.” (As a matter of fact I had not bestowed a second thought upon the poem, but was ashamed to acknowledge it.)

“When—oh! when can you decide?” she asked with much earnestness.

“To-morrow, I think”—for I fully intended to decline it.

She seemed deeply disappointed. Her lip quivered as she held down her head, and her form trembled with agitation. I could not understand her emotion, but, of course, said nothing to show that I observed it.

“Could you not give me an answer to-day—this afternoon,” the girl eagerly urged.

“Yes,” I said, “as you seem so very anxious, if you will give me your address, I shall take or send an answer before four o’clock. Where do you reside?”

“Do you know Forshay’s Cottages? They are a long way up Yates Street. We occupy No. 4.”

Forshay’s cottages were a collection of little cabins that had been erected on a lot at the corner of Cook and Yates Streets. They have long since disappeared. They were of one storey, and each cottage contained three rooms—a kitchen and two other rooms. I could scarcely imagine a refined person such as the lady before me occupying those miserable quarters; but then, you know, necessity knows no law.

The girl thanked me, and Barclay accompanied her to the corner of Yates Street. He seemed to be trying to induce her to do something she did not approve of, for she shook her head with an air of determination and resolve and hurried away.

Barclay came back to the office and said: “I am English myself, but the silliest creature in the world is an Englishman who, having once been well off, finds himself stranded. His pride will not allow him to accept favours. I knew that girl’s father and mother in Grass Valley. The old gentleman lost a fortune at quartz mining. His partner, a Mr. Maloney, a Dublin man and graduate of Trinity College, having sunk his own and his wife’s money in the mine, poisoned his wife, three children and himself with strychnine, but the strangest part of the story is that three months ago the property was reopened and the very first shot that was fired in the tunnel laid bare a rich vein. Had Maloney fired one more charge he would have been rich. As it was he died a murderer and a suicide. Poor fellow! In a day or two I will tell you more. But let me return to the poetry. What will you do with it?”

“I fear I shall have to reject it.”

“No! No!” he cried. “Accept it! This morning I went to the home of the family, which consists of Mr. Forbes, who is crippled with rheumatism, his excellent wife, the young lady from whom we have just parted, and a little boy of seven. They are in actual want. I offered to lend them money to buy common necessities, and Forbes rejected the offer in language that was insulting. Now, I ask you, implore you, to go immediately to the cottage. Tell the girl that you have accepted the poem and give her this” (handing me a $20 gold piece) “as the appraised value of he production. Then return to the Hotel de France and await developments.”

I consented. The road was long and muddy. There were neither sidewalks nor streets, and it was a difficult matter to navigate the sea of mud.

The young lady answered my knock. She almost fainted when I told her the poem had been accepted and that the fee was $20. I placed the coin in her hand.

“Momma! Papa!” she cried, and running inside the house I heard her say, “My poem has been accepted, and the gentleman from the Colonist office has brought me $20.’

“Thank God!” I heard a woman’s voice exclaim. “I never lost faith, for what does Christ say, Ellen? ‘Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened.’ On this holy day—our Saviour’s birthday—we have sought and we have found.”

This was followed by a sound as of some one crying, and then the girl flew back to the door.

“Oh, sir,” she said, “I thank you from the bottom of my heart for your goodness.”

“Not at all,” I said. “You have earned it, and you owe me no thanks. I shall be glad to receive and pay for any other contributions you may send.” I did not add, though, that they would not be published, although they would be paid for.

A little boy with a troubled face and a pinched look now approached the front door. He was neatly but poorly dressed.

“Oh! Nellie, what is the matter?” he asked, anxiously.

“Johnnie,” answered Nellie, “I have earned $20, and we shall have a Christmas dinner, and you shall have a drum, too.” As she said this she caught the little fellow in her arms and kissed him, and pressed his wan cheek against her own.

“Shall we have a turkey, Nellie?” he asked.

“Yes, dear,” she said.

“And a plum-pudding, too, with nice sauce that burns when you put a match to it, and shall I have two helpings?” he asked.

“Yes; you shall set fire to the sauce, and have two helpings, Johnnie.”

“Won’t that be nice,” he exclaimed, gleefully. “But, Nellie, will Papa get medicine to make him well again?”

“Yes, Johnnie.”

“And mumma—will she get back all the pretty things she sent away to pay the rent with?”

“Hush, Johnnie,” said the girl, with an apologetic look at me.

“And you, Nellie, will you get back your warm cloak that the man with the long nose took away?” (Sorry, folks, but that’s a quote.—TW)

“Hush, dear,” she said. “Go inside now; I wish to speak to this gentleman.” She closed the front door and asked me, all the stores being closed, how she would be able to get the materials for the dinner and redeem her promises to Johnnie.

“Easily enough,” said I. “Order it at the Hotel de France. Shall I take the order?”

“If you will be so kind,” she said.” Please order what you think is necessary.”

“And I—I have a favour to ask of you.”

“What is it?” she eagerly inquired.

“That you will permit me to eat my Christmas dinner with you and your family. I am almost a stranger here. The few acquaintances I have made are dining out, and I am at the hotel with Mr. Barclay, whom you know, and, I hope, esteem.”

“Well,” she said, “come by all means.”

“And may I bring Mr. Barclay with me? He is very lonely and very miserable. Just think that on a day like this he has nowhere to go but to an hotel.”

She considered a moment before replying; then she said, “No, do not bring him—let him come in while we at dinner, as if by accident.”

I hastened to the Hotel de France, and soon had a big hamper packed with an abundance of Christmas cheer and on its way upon the back of an Indian to the Forbes home.

I followed and received a warm welcome from the father and mother, who were superior people and gave every evidence of having seen better days. The interior was scrupulously clean, but there was only one chair. A small kitchen stove, at which the sick man sat, was the only means of warmth. There were no carpets, and, if I was not mistaken, the bed coverings were scant. The evidence of extreme poverty was everywhere manifest. I never felt meaner in my life than when I accepted the blessings that belonged to the other man. Mr. Forbes, who was too ill to sit at the table, reclined on a rude lounge near the kitchen stove. Just as dinner was being served there came a knock at the door. It was opened and there stood Barclay.

“I have come,” he said, “to ask you to take me in. I cannot eat my dinner alone at the hotel. You have taken my only acquaintance (pointing to me) “from me, and if Mr.. Forbes will forgive my indiscretion of this morning I shall be thankful.”

“That I will,” cried the old gentleman, from the kitchen. “Come in and let us shake hands and forget our differences.”

So Barclay entered, and we ate our Christmas dinner in one of the bedrooms. It was laid upon the kitchen table, upon which a table cloth, sent by the thoughtful hosts at the hotel, was spread. There were napkins, a big turkey, and claret and champagne, and a real, live polite little Frenchman to carve and wait.

Barclay and I sat on the bed. Mrs. Forbes had the only chair. Johnnie and his sister occupied the hamper. Before eating, Mrs. Forbes said grace, in which she again quoted the passage from the Scripture with which I began this narration. For a catch-up meal it was the jolliest I ever sat down to, and I enjoyed it, as did all the rest. Little Johnnie got two helpings of turkey and two helpings of pudding, and then he was allowed to sip a little champagne when the toasts to the Queen and the father and mother and the young man and rising poetess of the family were offered. Then Johnnie was toasted, and put to bed in Nellie’s room.

Next it came my turn to say a few words in response to a sentiment which the old gentleman spoke through the open door from his position in the kitchen, and my response rebounded in prevarications about the budding genius of the daughter of the household. Then I called Barclay to his feet, and he praised me until I felt like getting up and relieving my soul of the weight of guilt, but I didn’t, for had I done so the whole affair would have been spoiled.

Barclay and I reached our quarters at the Hotel de France about midnight. We were a pair of thoroughly happy mortals for had we not, after all, “dined out,” and had we not had a royal good time on Christmas Day, 1860?

The morrow was Boxing Day, and none of the offices were opened. I saw nothing of the Princess; but I observed Bertie, the sweet “child,” as he paid frequent visits to the bar and filled himself to the throttle with brandy and water and rum and gin, and bought and paid for and smoked the best cigars at two bits each. As I gazed upon him the desire to give him a licking grew stronger.

By appointment Barclay and I met in a private room at the hotel, where he unfolded his plans.

“You must have seen,” he began, “that Miss Forbes and I are warm friends. Our friendship began six months ago. I proposed to her, and was accepted, subject to the approval of the father. He refused to give his consent because, having lost his money, he could not give his daughter a dowry. It was in vain I urged that I had sufficient for both. He would listen to nothing that involved an acceptance of assistance from me, and he left [for] Vancouver Island to try his fortunes here. He fell ill, and they have sold or pawned everything of value. The girl was not permitted to bid me good-bye when they left Grass Valley. After their departure the discovery of which I have informed you was made in the Maloney tunnel, and as Mr. Forbes has held on to a control of the stock in spite of his adversities, he is now a rich man. I want to marry the girl. As I told you, I proposed when I believed them to be ruined. It is now my duty to acquaint the family with their good-fortune, and renew my suit. I think I ought to do it to-day. Surely he will not repel me now when I take that news to him as he did so on Christmas morning when I tendered him a loan.”

I told him I thought he should impart the good news at once and stand the consequences. He left me for that purpose. As I walked into the dining-room, I saw the dear “child” Bertie leaning over the bar quaffing a glass of absinthe. When he saw me he gulped down the drink and said:

“Mamma would like to speak with you.”

I recalled the adventure with the eyes and hesitated. Then I decided to go to room 12 on the second flat and see the thing out. A knock on the door was responded to with a sweet, “Come in.” Mme. Fabre was seated in an easy chair before a cheerful coal fire.

She rose at once and extended a plump and white hand. As we seated ourselves she flashed her burning eyes upon me and said:

“I am so glad you have come. In the first place I may tell you now I have found the man who owns the shares. He is here in Victoria with his family. He is desperately poor. A hundred dollars if offered would be a great temptation. I will give more—five hundred if necessary.”

“The property you told me of the other day is valuable, is it not?” I asked.

“Yes—that is to say, we think it is. You know that mining is the most uncertain of all ventures. You imagine you are rich one day and the next you find yourself broke. It was so with my husband. He came home one day and said, ‘We are rich”; and the next he said, ‘We are poor.’ The Maloney mine looks well, but who can be sure? When I came here I thought that if I found the man with the shares I could get them for a song. I may yet, but my dear child tells me that he has seen here a man from Grass Valley named Barclay, who is a friend of that shareholder, and,” she added, bitterly, “perhaps he has got ahead of me. I must see the man at once and make him an offer. What do you think?”

“I think that you might as well save yourself further trouble. By this time the shareholder has been apprised of his good fortune.”

“What!” she exclaimed, springing to her feet and transfixing me with her eyes. “Am I, then, too late?”

“Yes,” I said, “you are too late. Forbes—that is the man’s name—knows of his good fortune, and I do not think he would now sell at any price.”

The woman glared at me with the concentrated hate of a thousand furies.

Her great eyes no longer bore an expression of pleading tenderness—they seemed to glint and expand and to shoot fierce flames from their depths. They terrified me. How I wished I had left the door open.

“Ah!” she screamed. “I see it all now. I have been betrayed—sold out. Have you broken my confidence?”

“I have never repeated to a soul what you told me,” I replied quietly.

“Then who could have done it?” she exclaimed, bursting into a fit of hysterical tears. “I have come all this way to secure the property and now find that I am too late. Shame! Shame!”

“I will tell you. Barclay is really here. He knew of the strike as soon as you did. He is in love with Miss Forbes and has followed the family to tell them the good news. He is with the man at this moment.”

“Curse him!” she cried through her set teeth.

I left the woman plunged in a state of deep despair. I told her son that he should go upstairs and attend to his mother, and proceeded to the Forbes cottage. There I found the family in a state of great excitement, for Barclay had told them all, and already they were arranging plans for returning to California and taking steps to reopen the property.

Miss Forbes received me with great cordiality, and the mother announced that the girl and Barclay were engaged to be married, the father having given his consent. The fond mother added that she regretted very much that her daughter would have to abandon her literary career, which had begun so auspiciously through my discovery of her latent talent.

I looked at Barclay before I replied. His face was as blank as a piece of white paper. His eyes, however, danced in his head as if he enjoyed my predicament.

“Yes,” I finally said, “Mr. Barclay has much to be answerable for. I shall lose a valued contributor. Perhaps,” I ventured, “she will continue to write from California, for she possesses poetical talent of a high order.”

“I shall gladly do so!” cried the young lady, “and without pay, too. I shall never forget your goodness.”

I heard a low, chuckling sound behind me. It was Barclay swallowing a laugh.

They went away in the course of a few days, and we corresponded for a long time; but Mrs. Barclay never fulfilled her promise to cultivate the muse, nor in her letters did she refer to her poetical gift. Perhaps her husband told her of the pious fraud we practised upon her on Christmas Day, 1860. But whether he did or not, I have taken the liberty, forty-four years after the event, of exposing the part I took in the deception and craving forgiveness for my manifold sins and wickedness on that occasion.

What became of the Russian princess with the pretty manners, the white hands and the enchanting eyes, and the sweet “child” Bertie? They were back at Grass Valley almost as soon as Forbes and Barclay got there, and from my correspondents I learned they shared in the prosperity of the Maloney claim, and that Mme. Fabre and her son returned to Russia, to live and die among their noble kin.

* * * * *

Merry Christmas to all and may 2021 be kind!

--An antique Christmas card from the author's collection.

Have a question, comment or suggestion for TW? Use our Contact Page.