Charles Eugene Bedaux and His Champagne Safari

This French-American character was right out of a dime novel—or a 1930s movie script.

In his less than 60 years he was everything from dishwasher, pimp and Foreign Legionnaire to the friend of British royalty and the fifth richest man in the United States.

Rich adventurer Charles Bedaux, left, watches as a film crew documents his overland expedition in northern B.C. —Frank Swannell photo, BC Archives

Yet, for all these achievements, he died, supposedly by his own hand, in a prison cell while awaiting trial for treason.

Who could have foreseen any of this in 1934 when he came to British Columbia in charge of his grandly named Bedaux Canadian Sub-Arctic Expedition consisting of 100 people, most of them hired locally. It was really a promotional tour for Citroen half-track cars—and a romp for a fun-seeking, eccentric millionaire—but an incredible trail-blazing tour through virgin wilderness of northern B.C., all the same.

* * * * *

Last September, Anthony Rota, Speaker of the House of Commons, issued a public apology then resigned after a furore erupted over his having invited and acknowledged a man who was given a standing ovation by members of parliament, then revealed to have served in the infamous Nazi Waffen SS. Rota claimed he was unaware of “the full extent of Hunka's wartime affiliations...”

In January, the Manitoba government and the Winnipeg Art Gallery “removed honours” given Ferdinand Eckhardt over concerns he was a Nazi sympathizer during the 1930s. “This is a person who, to speak very frankly, pledged an oath of allegiance to [Adolf] Hitler, and he has no place being honoured in the public sphere here in Manitoba,” said Premier Wab Kinew.

Adding insult to injury, he theatrically drew a line through Eckhardt’s name in a book listing the recipients of the Order of the Buffalo Hunt. Eckhardt, who’d emigrated to Canada after the war and served for 20 years as a director of the art gallery, died in 1995 and with him his Order of Canada.

Previously, in November 2021, it was reported in the Alaska Highway News that “Mount Bedaux and the Bedaux Pass in northeastern British Columbia may soon have their names removed due to concerns the landmarks commemorate an accused war criminal.”

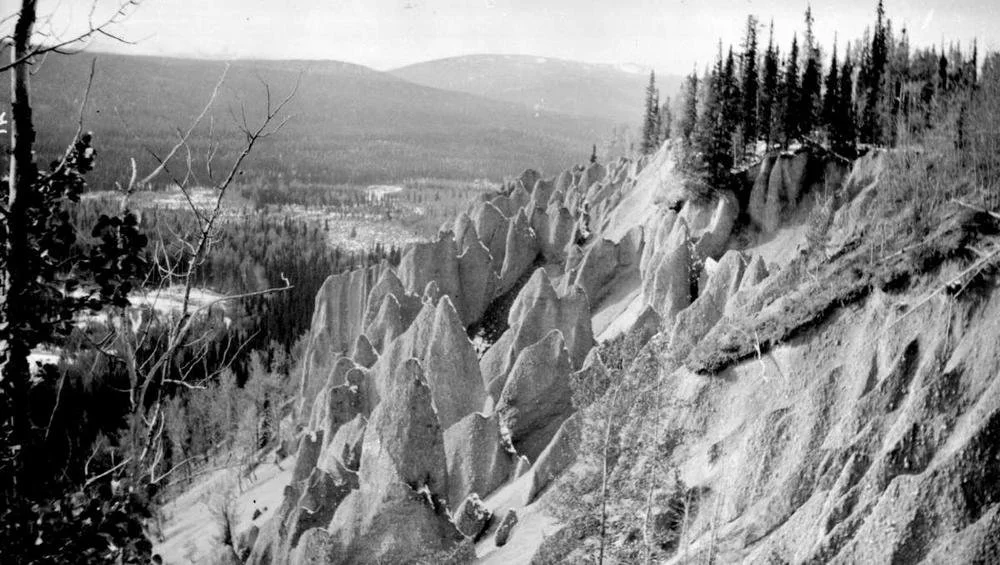

Kwadacha Wilderness Provincial Park. —BC Government photo

These geographical features at the headwaters of the Muskwa River in Kwadacha Wilderness Provincial Park commemorate the subject of this week’s Chronicles, French-American industrialist Charles Eugene Bedaux.

They’d been drawn to the attention of the B.C. Geographical Names office by an unnamed B.C. resident who felt the names were inappropriate considering Bedaux’s ultimate disgrace as an accused traitor or, at the very least, a Nazi sympathizer.

Charles Bedaux, second from left, chats with a local family in the wilds. —BC Archives

“Before any naming decisions are made, it is important to ascertain if the decision would support or conflict with the heritage values of the area,” said provincial toponymist Carla Jack. “The request currently under consideration is to rescind the two names and does not include replacing the names at this time.”

That was two years ago. As of July 2022, it was reported that no action had been taken on the renaming of 6,741 ft / 2,055 m Mt. Bedaux and, presumably, Bedaux Pass.

How ironic then that this same BC Geographical Names office had long listed Charles Bedaux, with his champagne, caviar, mistress and maid, as “one of the most flamboyant explorers in Canadian history” on its website.

* * * * *

Paris-born in 1886, the son of a railway worker, Bedaux was a school dropout by his early teens. He seemed headed for a life of menial jobs until he was befriended by a pimp. Henri Ledoux, later murdered, introduced the young novice to (among other things, no doubt) “proper dress, confidence and street-fighting”. But, instead of his becoming a thug, these qualities later served him to good purpose after he emigrated to the U.S. in 1906.

Initially, there was a succession of labouring jobs in Hoboken, N.J.: bottle-washer, sandhog and mill worker, as well as marriage and a son. None of these even hinted at his future: becoming fabulously rich as an industrial consultant, one who’d hobnob with British royalty and be befriended by leading German fascists.

But, obviously ambitious, he was on his way up in the world, first working for a chemical company then a pharmaceuticals firm before becoming an interpreter for an Italian engineering company. This role took him to Europe on business and to yet another job, for a consulting agency in 1913.

All of this appears to have become boring however as, in August 1914, on the eve of the First World War, he joined the French Foreign Legion. But not for long; soon discharged on medical grounds, he rejoined his former engineering employers and returned to the States, this time to Michigan where, apparently still restless, he divorced and remarried.

Somewhere along the way, he’d begun to study scientific management efficiency as measured by time, motion and environment. Strongly influenced by F.W. Taylor’s treatise Shop Management, and Charles E. Knoeppel’s study of industrial layout and routing, Bedaux studied and polished the concept of maximizing by rating workplace and employee efficiency.

He called his idea, which some historians have criticized as being unoriginal, simply cobbled together from previous work systems, the Bedaux System of Human Power Measurement.

The key was the Bedaux Unit, defined as a universal measure for all forms of manual work. (Certainly, Bedaux had had had firsthand opportunities to study and to form ideas about manual labour in his travels.) His system promised to reduce corporate costs and increase production by measuring company time in seconds, not minutes or hours. It set production goals for employees, most of whom up until that time, had been paid for piece-work, with the offer of bonuses for those who exceeded expectations.

Bedaux has to have been a born salesman. One of his first large corporate clients was the Eastman Kodak camera and film giant. More large clients followed and by 1926 the Bedaux ‘B System’ had been implemented on both sides of the Atlantic. To emphasize his firm’s emphasis on the micro-management of time, his company used an egg timer as its logo.

In just a decade Bedaux Internationale had established branches in North America, Europe, Africa, India, Australia and Asia, with some of the largest corporations of the day for clients.

Not that his approach to production efficiency had won him friends in all quarters. Bedaux’s system was, in fact, so hated by labour that there were work massive work stoppages and lengthy strikes in various American, British and European industries, from the making of soups, candies, automobiles and textiles to forestry and mining.

But resistance in offices and factories and fields proved futile and one industry after another embraced the Bedaux Unit. The money rolled in and Bedaux, the school dropout and menial labourer who’d once flirted with street criminals, became filthy rich—the fifth richest man in all America.

Ironically, he who’d made his living and his fortune by devising work system efficiency for others, now had the means and time to indulge in leisure. Somehow, in collaboration with the Peugot automobile owner and friend Andrew Citroen (whose company is the oldest automobile manufacturer in the world, by the way) he conceived the idea of (in his words) “a land route to Alaska,” by trail-blazing across northeastern British Columbia with half-track vehicles. This was no less than 1500 miles (2400 km).

It should be noted that Bedaux was no stranger to northern British Columbia, having visited twice before, in 1926 and 1931, leading some to suspect that, even before his business and personal relationships with Fascist governments, he had sinister motives.

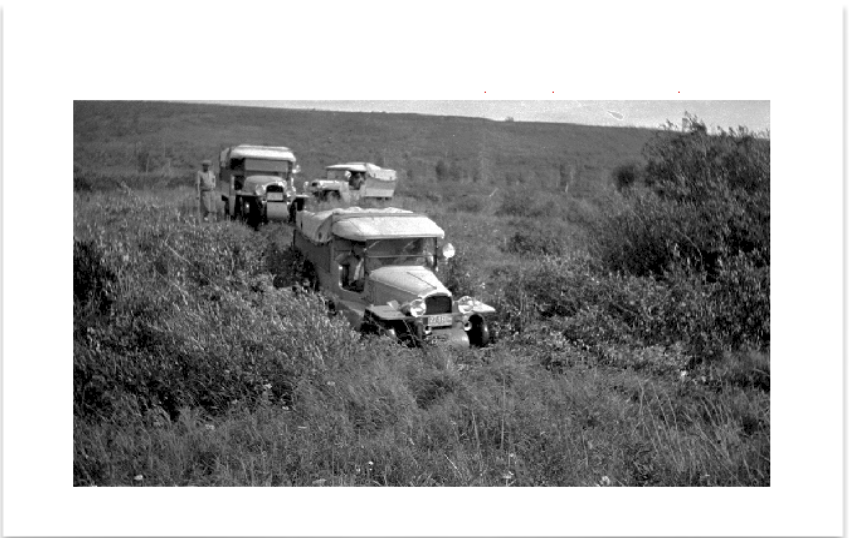

Looking much like domestic Fords, Bedaux’s French-built Citroen half-tracks make their way through brush which was nothing like some of the terrain they had to endure on their way west. —Wikipedia

He and wife Fern had already made two cross-country forays by vehicle: 9500 miles of jungle and Sahara Desert from Mombasa, Kenya to Casablanca in 1929-30, and a second 9500 miles from Cape Town to Kenya. By comparison, 1500 miles of mountains, rivers and forests in northern British Columbia, even though mostly uncharted and offering nothing in the way of roads, likely seemed to be less daunting.

The Canadian government was so enthused at Bedaux’s arrival it provided him with the assistance of two departmental geographers; one of them, Frank Swannell, took most of the still photos that survive of the expedition.

After a send-off including a parade and a farewell address by Alberta’s lieutenant-governor, the expedition, with Bedaux and coterie primed on champagne and caviar, left Edmonton on July 6, 1934 with the purported aim of driving “a fleet of automobiles from Edmonton through the unmapped northern Rocky Mountain Divide, thence by way of Telegraph Creek to Alaska, a distance of 2400 km”.

Bedaux’s intended itinerary was thus: in Alberta, Edmonton to Athabasca to Grand Prairie; in B.C., Dawson Creek to Fort St. John then northward over the Rockies through Sifton Pass to Dease Lake and on to the Stikine River to Telegraph Creek then, finally, to the Pacific Ocean. By July 17th, despite continuous rain, they’d crossed into B.C., en route to Fort St. John where they rested and restocked.

An example of the wild terrain that the expedition encountered. —BC Archives

However, in mid-September, despite public predictions that the expedition was within a few weeks of its destination, Bedaux pulled the plug in when advised against continuing by surveyor Swannell because it was so late in the season and many of the pack horses were ill and dying. They’d been on the trail for four months.

BCG Names office has dismissed the Bedaux expedition as being “over-equipped, ill-equipped and peppered with staged mishaps,” the latter for the benefit of accompanying Hollywood cinematographer Floyd Crosby who’d later win an Academy Award for his work on the classic western High Noon.

(Crosby’s celluloid, found years later “in a basement in Paris,” ultimately did make it to ‘Hollywood’—60 years later—when Canadian director George Ungar incorporated much of the original footage in a television documentary, The Champagne Safari.)

As for the pioneering Citroen half-tracks, they’d already been sacrificed for want of greater media attention. With Crosby manning his camera, two were driven over cliffs and a third was left stranded on a sandbar after a failed attempt to blow it up with explosives. All this was intended for public release to satisfy Bedaux’s apparent craving for attention, and did in fact gain the expedition international publicity for its staged thrills and spills. The remaining two half-tracks were ultimately abandoned and found during construction of the Alaska Highway in the 1940s. One, recovered for posterity, is in a museum in Moose Jaw, Sask.

* * * * *

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor on vacation in the Mediterranean in 1936 and Charles Bedaux’s chateau where they were married. —Wikipedia

By then, Bedaux had returned to live in France with his wife in a renovated 16th century chateau. It was there that, in June 1937, Charles and Mrs. Bedaux hosted the wedding of Prince Edward, the Duke of Windsor, and American divorcee Wallis Simpson.

In mid-1937, ever the entrepreneur, Bedaux invited the vice-regal couple to accompany him on a trip to Germany which, already firmly in the grip of the Nazi party, gave them red carpet treatment, including an SS regimental band playing God Save the King. All of this was in stark contrast to the chilly reception the commoner Duchess had been accorded in England.

Likely as part of Bedaux’s business activities, their tour included visits to factories and mines—even a training school for the SS which would soon become the Nazi juggernaut for Jewish extermination.

But that was still in the future. In the meantime, Bedaux, the Duke and Duchess planned an extended tour of the United States—only to have to cancel because of widespread labour and press protests against Bedaux and his system which had become identified with fascism. Those companies which continued to practise the Bedaux Unit found it necessary to make it more palatable, if only cosmetically, to keep the peace with their workers.

By this time, Bedaux, although still rich, still successful, was internationally despised.

The Second World War and France’s surrender found him still in residence in his chateau and still on friendly terms with the occupying Germans, to the point of his acting as an advisor to the collaborationist Vichy government. Even then, French coal miners rebelled against his work system.

If collaborating with the Germans wasn’t bad enough—untold numbers of French men and women were equally guilty—he crossed the line by conspiring with the Germans to capture a major British-owned oil refinery at Abadan in advance of a planned invasion. The plan had to be abandoned after the rout of General Rommel in North Africa and battlefront reverses on the Russian front.

Bedaux’s rags-to-riches world came tumbling down in December 1942 with the successful Allied invasion of North Africa. Even though he’d commenced correspondence with the British and the Americans whose intelligence agencies had begun compiling a file on him, he was arrested by the Free French. Handed over to the Americans, he was imprisoned without charge then transferred him to the U.S. to face charges of trading with the enemy and treason.

While in FBI custody in Florida, he took an overdose of barbiturates and made nation-wide newspaper headlines for the last time. It has long been suspected that Bedaux was, in fact, silenced or encouraged to commit suicide before he could tarnish top-ranking American financiers by detailing their pre-war business dealings with the Nazis.

The only things this experimental mobile monstrosity shared with the off-road vehicles used by Bedaux are its manufacture by Citroen and its half-tracks. This one was meant to be an armoured car. —Wikipedia

* * * * *

What historical significance, if any, does the failed Bedaux overland expedition have today?

Because it preceded the building of the Alaska Highway during the Second World War, Bedaux’s expedition does have merit according to Fort St. John North Peace Museum curator Heather Sjoblom because it contributed to the history of the region despite its failure.

“He really did make a difference in this area,” she told News reporter Tom Summer, “but maybe in some ways it would be better to name them [Mount Bedaux, Bedaux Pass] after someone local who’s potentially more worthy. Bedaux’s expedition here in 1934 brought a ton of attention to the area and really made a difference for the average people who were living here in the midst of the Great Depression.”

More recently—just last month—the Fort St. John Museum hosted a documentary night to celebrate the 90th anniversary of ‘The Champagne Safari, a look at eccentric millionaire Charles Bedaux, and the 1934 expedition he funded.”

As curator Sjoblom told the Prince George Citizen: "We wanted a way to kind of mark the 90th anniversary, and this is kind of the best way, although we have a lot of photos in our collection and a small exhibit that includes the Bedaux Expedition, we don't have the array of film footage that's on the DVD and the personal interviews and so on."

"Not that many expeditions, one, come through this area, and two, bring stuff like champagne and caviar, and a collapsible bathtub, as well as Bedaux's wife and mistress," she said. "So, it's quite a different story than one is used to.”

A display has also been set up at the North Peace Regional Airport to showcase the people and items involved in the expedition. Proving that, at least in Prince George, Charles Eugene Bedaux is neither forgotten nor totally condemned to infamy.

On an international scale, he has been ridiculed by Charlie Chaplin, fictionalized by novelist Upton Sinclair and reviled by satirist George Orwell. In Tours, France, the Avenue Charles Bedaux was renamed in 2018 and his Chateau de Cande, where the Duke and Duchess of Windsor were married, is open to the public. It still displays many of Bedaux’s personal possessions.

* * * * *

* This week’s Chronicle is compiled from numerous sources; to give due credit, I followed, for the sake of convenience, the timeline of a well-researched Wikipedia post.